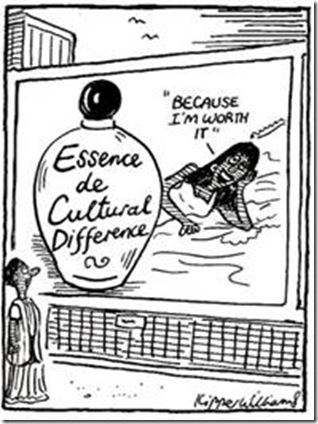

“Adults, older girls, shops, magazines, newspapers, window signs—all the world had agreed that a blue-eyed, yellow-haired, pink-skinned doll was what every girl child treasured” (20). Claudia says that she was not old enough to have the idea that white equals beautiful the same way her older friends and family members had, hence why she disliked the white, blonde, and blue-eyed doll she was given. It is implied that she, like everyone else in the community, would come to recognize these features as standards of beauty. Pecola is the greatest example of this, as she deeply desires blue eyes. For example, Pecola “was fond of the Shirley Temple cup and took every opportunity to drink milk out of it just to handle and see sweet Shirley’s face” (23). The message that whiteness is the most desirable appearance is not only projected within the U.S. but also abroad. As a result of colonialism and the more modern globalization, whites have propagated images of themselves and Western nations continue attempts to dominate others around the world. Through force and more indirect cultural imperialism, whiteness has become the beauty ideal.

The Bluest Eye depicts many instances of racism and its effects. For example, when Cholly is forced to have sex at gunpoint while two white men watch, this affects him for life. “The flashlight wormed its way into his guts and turned the sweet taste of muscadine into rotten fetid bile” (148). Pauline is deeply affected by the media. “She was never able, after her education in the movies, to look at a face and not assign it some category in the scale of absolute beauty, and the scale was one she absorbed in full from the silver screen” (123). Both of these characters are tragically altered by their experiences in a society that deems whiteness as superior.

Another aspect of the novel is related to the history of colonialism and the way in which developed nations ignore developing nations. “At some fixed point in time and space he senses that he need not waste the effort of a glance. He does not see her, because for him there is nothing to see” (48). Just as Mr. Yacobowski refuses to see Pecola because of the color of her skin, Western nations have historically practiced colonialism and justified their actions based on the appearances and cultures of the people they dominated. Still today, developing nations are not considered large international players; their voices are often ignored.

Furthermore, by exploring different points of view, the book addresses how a one-sided narrative is never the entire truth. Claudia thinks, “But was it really like that? As painful as I remember? Only mildly. Or rather, it was a productive and fructifying pain” (12). Additionally, Morrison writes that it, “gives the reader pause about whether the voice of children can be trusted at all or is more trustworthy than an adult’s” (213). In the same way the novel questions truth based on perspective, our histories have been written from a white male perspective that cannot come close to the truth since it is one-sided. Developed nations dominate and disseminate their histories, ignoring any flaws, never giving a voice to others around the world.

This is related to previous readings about sexuality. Walker writes, “It is obvious that the suppression of sexual agency and exploration, from within or from without, is often used as a method of social control and domination” (22-23). Racism, like the suppression of sexual agency, is used as a means of social control around the world. Internalized racism, as evidenced by The Bluest Eye, is extremely detrimental and is a result of colonialism and the globalization and cultural imperialism of today.

-Erica

Kim Kardashian before and after photo retouching. Her waistline is trimmed and her skin is lightened.

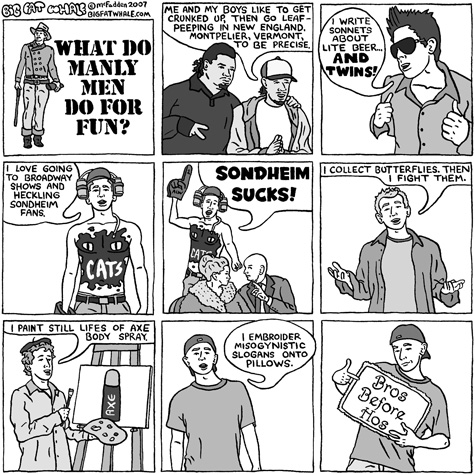

The new Dora the Explorer represents homogenization in the sense that Dora used to be a blocky tomboy but is now a slender pre-teen.